The Art of Letting Go: Teikan and Japan’s Lost Generation

Finding Peace in What We Cannot Change...

In Japanese, the word teikan (諦観) captures the quiet acceptance of reality—embracing life as it is, rather than clinging to what we cannot change.

Far from mere “giving up,” teikan is a lens of clarity and resilience.

Across time and cultures, the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius arrived at a similar truth in his Meditations: focus on what lies within your control and release the rest.

Today, as we chase success in a relentless world, these ideas feel both ancient and urgent.

For Japan’s 就職氷河期世代 (shūshoku hyōgaki sedai)—the generation shaped by the post-bubble job crisis—blending teikan with Stoicism is more than just philosophy; it is a survival strategy.

Teikan: Beyond Giving Up

Imagine a cherry blossom tree shedding its petals in spring.

Teikan is the moment you stop hoping the petals will cling to the branch and instead watch them drift away—trusting that nature will renew itself.

Rooted in Buddhist views of impermanence, teikan isn’t about despair; it is wisdom.

You don’t curse the rain—you simply wait out the storm.

Marcus Aurelius echoed this sentiment when he wrote, “You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.”

Both teikan and Stoicism urge us to shift our energy from futile resistance to cultivating inner calm.

Japan’s Lost Generation

Japan’s lost generation—those who came of age during the 1990s and early 2000s—faced a harsh reality. As the economy crumbled, stable jobs vanished, leaving an entire generation to navigate rejection, underemployment, and blame.

I, myself, am a product of this generation. I still remember the struggle of entering the workforce—rejection after rejection, doors closing before they could even open.

Decades later, the scars remain: lower wages, fractured career paths, and a lingering sense of having been left behind.

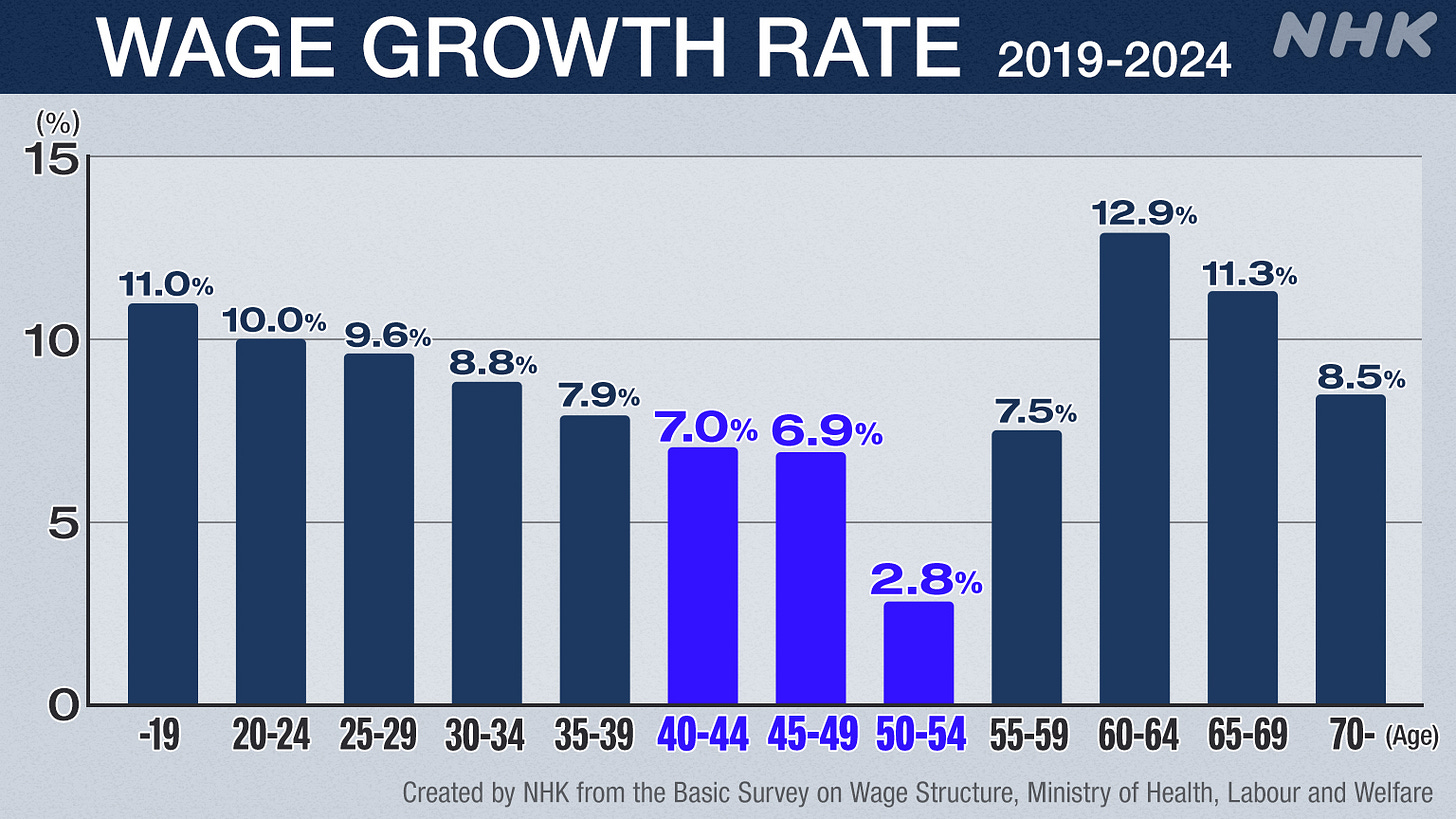

A recent NHK report underscores this reality: base pay increases vary dramatically depending on age, reflecting a system that continues to disadvantage those who started their careers in crisis.

This is where teikan comes in.

We cannot undo the economic collapse or the indifference we endured. Railing against it may feel satisfying, but it changes nothing.

As Marcus Aurelius wrote, “What need is there to weep over parts of life? The whole of it calls for tears.”

The struggle may be unfair—but fairness is never guaranteed. Teikan offers a way forward: let go of what cannot be controlled, and find strength in what remains.

A Modern Struggle

This philosophy resonates beyond Japan.

We all encounter moments when life refuses to bend to our will—whether it’s losing a job, facing shattered plans, or enduring global upheavals.

Today’s culture demands that we “fight harder.” But what if fighting only drains our energy instead of pushing us forward?

We’ve all been there. Stranded at an airport after a canceled flight. Taking the blame for a failed project at work.

Sometimes, the best way forward is to stop fighting.

That quiet “okay” is teikan. Bearing with patience what comes. It isn’t weakness—it’s strategy.

For Japan’s lost generation, teikan could mean releasing resentment toward a system that failed them.

It’s not about excusing neglect; it’s about refusing to be defined by it.

They cannot rewrite history, but they can shape their response.

The Strength in Acceptance

Both teikan and Stoicism demand courage.

Picture a river: you can’t stop its current, but you can learn to swim with it.

Marcus Aurelius advised, “Be tolerant with others and strict with yourself.”

For Japan’s lost generation—often misunderstood by younger peers and judged by older ones—this wisdom is crucial.

Letting go of the need to prove oneself can open space for genuine connection.

Learning to See

How do we practice teikan? It’s a gradual process.

For those who have endured hardship, it might mean reflecting on what they’ve gained rather than what they’ve lost: resilience, perspective, a story worth telling.

Marcus urged, “Ask yourself—what am I doing with my soul?”

Teikan grows when we pause to see reality as it is—not as we wish it to be.

Take time to be present. A small, deliberate nod to life’s flow.

A Quiet Invitation

Teikan and Stoicism, like old friends from different eras—one under a pagoda, the other in a Roman forum—remind us that life’s beauty lies in its limits.

Japan’s lost generation knows this better than most.

They didn’t choose their struggles, but they can choose how to face them.

And so can we all.

Next time the world feels unyielding, try this: breathe, observe, and ask—“What can I do with this?”

That simple act of letting go isn’t surrender—it’s strength.

That’s not just letting go—it’s living.